The two other versions of Gawain and the Green Knight I’ve looked at on this blog both use the original story as a sort of springboard and bounce off it to do their own thing - Stephen Weeks turned it into a swashbuckling romp, David Lowery into the sort of bad dream a Portland hipster might experience after going overboard on the artisan cheeses. This Thames TV version from 1991 stays much closer to the source material, and, despite a lower budget and less starry cast, it’s easily the best.

Screenwriter David Rudkin is mostly known nowadays for his famously spooky 1970s TV play Penda’s Fen, but he wrote a lot of other plays and adaptations, many dealing with eerie goings-on in rural settings - the type of thing that gets called ‘folk horror’ nowadays, though that’s not a term I like. Anyway, he clearly knows his stuff, turning in a taut hour-and-a-quarter retelling of Gawain with alliterative dialogue which echoes the original. The main change he makes is to open with Gawain setting out on his quest, and then have flashbacks fill in the details of the Green Knight’s arrival at Camelot and his head-chopping challenge. It’s a smart move, intercutting Gawain’s lonely journey through the wilds with the comforts of the court he’s left behind, and giving the film an atmosphere of unease right from the start. (Walter Fabeck’s subtle, creepy score helps too.)

That atmosphere continues when Gawain arrives at Hautdesert (though the castle isn’t named in the film, and it’s master, Sir Bertilak, is just listed in the credits as the Red Lord). Sir B welcomes the travel-weary Gawain to his Christmas celebrations, and proposes a game, just as the Green Knight did at the beginning. Each day Sir Bertilak will go out hunting, while Gawain rests in the castle: at the day’s end each man will give the other whatever he has caught. This goes on for three days, with Sir Bertilak presenting Gawain with a deer, then a boar, then a rather mangy fox, and getting in exchange first one, then two, then three kisses, which are what Gawain has received from Sir Bertilak’s lovely wife while he’s been gone. What Gawain doesn’t hand over is the green girdle she also gives him, which she promises will protect him from all harm. “Whatever man wears this about his waist, no knight on earth can mutilate, nor craft or cunning kill him.”

I could never understand why the other film versions shortened or sidelined this sequence, which has always seemed to me to be the meat of the story. It works tremendously well here. The warmth of the Christmas feasting and the cheerful comedy of the hunting game are undercut by the dangerous eroticism of the lady’s attempts to seduce Gawain, and by Gawain’s knowledge that, come New Year’s Day, he must ride the last few miles to the Green Knight’s lair and get his head lopped off. Maybe Gawain is a forerunner of the English tradition of Christmas ghost stories - there’s no ghost as such, but there’s the same contrast between the firelit cosyness and something old and ominous and unsettling.

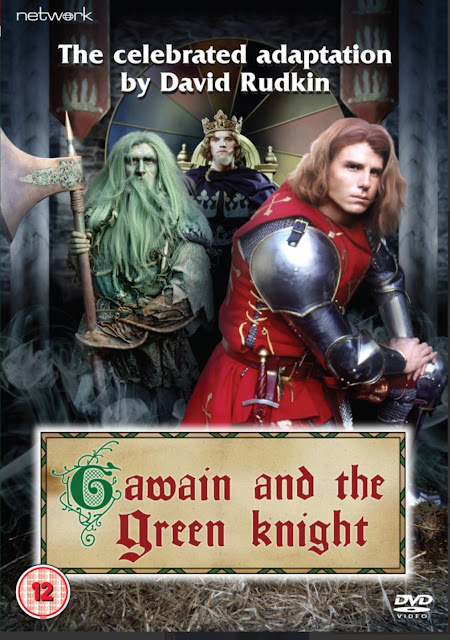

Production-wise, this Gawain is workmanlike rather than spectacular. Some of the video effects have aged poorly, but there aren’t many so it’s not a major problem, and the green-ness of the Green Knight himself is bracingly weird. The costumes at Camelot look as if they’re fresh off a rack at Angel’s and need to be returned next morning without a smudge on them. The lighting is a bit flat too, as older TV lighting often is. There are some good landscapes (Yorkshire, I think), but it’s unfortunate that the hunting scenes are filmed in autumn rather than winter. Director John Michael Phillips does his best to keep the camera pointing at dead branches and holly trees, but it clearly isn’t Christmas, and in a story that is so much about the turning of the year that seems a shame. But Hautedesert is warmly lit and livelier than Camelot, and Gawain’s red livery looks great against the sombre shades of the moors and forests. I liked his shield a lot - it has his pentagram symbol on the front, and on the inside is an icon of the Virgin Mary, so he can prop it up and use it as a portable shrine when he says his prayers in the wilderness: just what every good knight errant needs.

The cast isn’t starry, although Malcolm Storry as Sir Bertilak/the Green Knight and Valerie Grogan as his wife will both be fairly familiar faces if you watched much TV in the ‘90s. So is Marc Warren, who plays a very youthful King Arthur (for one disconcerting moment I thought he was an uncannily well-preserved Malcolm McDowell). Jason Durr, at the beginning of a long and distinguished TV career, makes a suitably handsome and troubled Gawain.

The film doesn’t stay slavishly true to the poem. In that, the mysterious old woman Gawain sees at Hautdesert is finally revealed to be Morgan le Fay, the author of the whole adventure. Here she is present, whispering her instructions to the Red Lord and his lady, but we never learn who she is. It’s a sound decision, I think, making the Green Knight all the more mysterious.

This is the power of the story, I think; the sense that just beyond the well-ordered bounds of Camelot, and just beneath the traditional, Christian quest story, there lurks something wild, unheimlich, and inexplicable. David Rudkin has done the Gawain Poet proud.

The Green Knight’s game is concluded, Gawain rides home, and in his honour Arthur declares that all his knights shall wear green sashes. But to Gawain it has become a badge of shame, or at least of doubt, for ever reminding him of how ‘One mid-winter morning I met my master on a mountainside, and he invested me with emblem of the order of imperfect man.’

Happy New Year and, if you have been, thanks for reading!

Comments