|

| Poster by Sarah McIntyre |

I’d decided to go for an Arthurian story while watching loads of Arthurian films and TV shows for this blog a few years ago. Historical but not demanding historical accuracy, often silly yet still deeply serious, they felt like something we might be able to achieve on our pocket-money budget. Once that decision was made, the writing process went something like this:

1. I can’t adapt an actual Arthurian tale because I can’t afford loads of knights and battles and a round table…

2. So what if it’s a film about women? That would be a bit different, and frocks are cheaper than armour…

3. Who’s the first female character who springs to mind when you think about Arthurian legend? Well, Gwenevere, obvs.

4. Ah, but I want Jo Neary to be in my film, because she’s a genius. And I can’t see her as Gwenevere - she’s too funny.

5. So maybe Jo plays Gwenevere’s lady in waiting. And they’re off on a journey in the wilderness together because we can’t afford Camelot…

… and the rest just fell into place around that very quickly.

Unlike a book, where your imagination is the only limit, you’re constrained by cost and practicality when you’re writing a screenplay. I reckoned we could afford five or six actors, and I knew we could use the camping barn at Great Houndtor for our interiors, so I built the story around those, frequently stopping to ask, how are we actually going to do this? I kept dialogue to a minimum, mainly because I thought it would be difficult to record and sync with the visuals (though it turned out that’s actually pretty easy.) I tried not to explain too much, because I wanted it to work like a dream - a procession of images whose meaning isn’t always clear. (But I chickened out a bit, so it has ended up with a fairly conventional structure, and plenty of gags.)

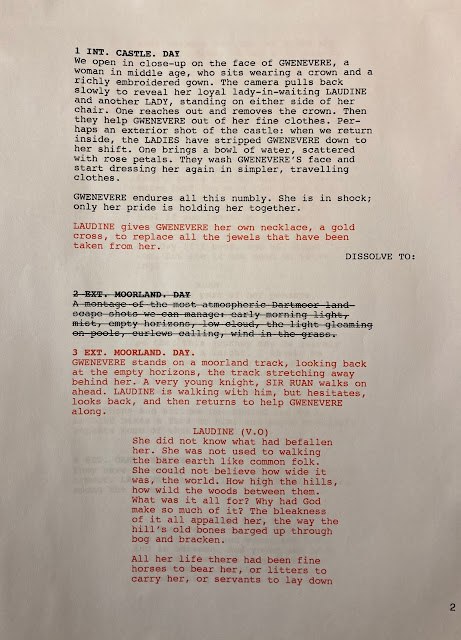

Here’s page 1 of the final draft.

We’d actually shot a couple of scenes by the time I printed this one off - the deleted Scene 2 was taken out because I’d seen Laura Frances Martin as Gwenevere and she was so good that I realised a cut between two close-ups of her face would be far stronger than interposing the landscape stuff. And the bit in red where Laudine gives her the gold cross was invented by Jo Neary to cover a continuity error (we were half way through that scene when we noticed the cross Jo had been wearing around her neck had slipped off and vanished down her bodice.) It was a happy accident, because we turned the exchange of the cross into a sort of motif which recurs later in the film.

About six months before the shoot I went through the screenplay and drew storyboards for most of it as a way of visualising how each scene would work in my own mind. But once we were in the (barely) organised chaos of Big Week there was scarcely time to glance at the storyboards, and often the shots I’d imagined wouldn’t have been feasible anyway. But writing and then drawing the story meant I had all the details very clearly in my head, so whatever we were filming I always knew where the characters had come from, what they were feeling, where they were going next, etc.

Sometimes I did have to come up with emergency storyboards to keep things clear while we were shooting. If you have two characters talking or confronting each other it’s important that, in their close ups, they look off opposite sides of the screen. I can barely tell left from right at the best of times, so I got very confused and ended up drawing helpful diagrams on the lid of the props box and finally on my hand. (This is probably the same trick that Steven Spielberg and all those fellas use.)

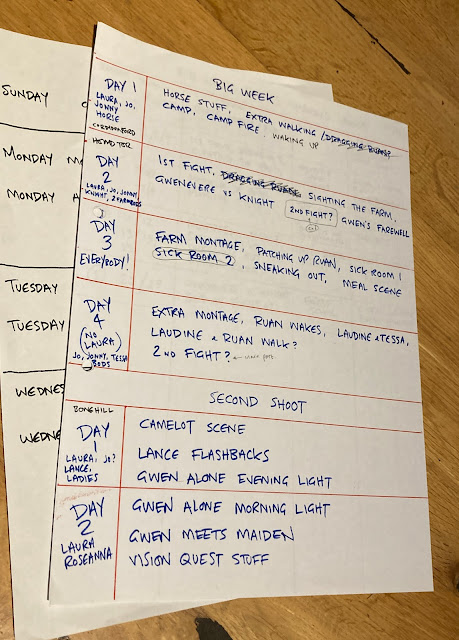

The other thing that really helped was the complicated schedules I had to draw up before production, working out which actors and groups of actors were available on which days, and which scenes it made sense to shoot together. I didn’t think at the time that it was part of the creative process - it just felt like admin - but in retrospect it really helped me know the story inside out.

We stuck fairly closely to the screenplay, I think. Here and there a line or scene got cut because it didn’t work, or we didn’t get a good enough take. Some things were simplified because we ran out of time or couldn’t get the combinations of actors we needed together. The horse we had arranged for the opening scenes had to be written out hastily a few days before we started. And the actors often came up with better ideas than mine - many of the best lines and bits of business are theirs. There’s a scene where Jo’s character, lost in the wilds, prays to Saint Christopher for help…

We agreed that someone in the Middle Ages would probably have such an unquestioning belief in saints and prayer that it would feel as logical as phoning a helpline, so she threw in a casual ‘thank you’ at the end which I wound up using to round off the whole scene.

And then, in the edit, lots of things changed, because there were scenes I realised we didn’t need, and scenes that worked better in different places, and whole sequences that were assembled out of loose footage we’d shot not really knowing what we were going to do with. So at that point the screenplay was basically thrown away. But it had served its purpose by then.

Comments