Many place-names in the Autumn Isles reference Saint Chyan, the 9th Century missionary who introduced Christianity to the islands. (Sundown Watch, where Utterly Dark lives, stands upon a cliff called Saint Chyan’s Head.) In an early version of the third Utterly Dark book, Utterly Dark and the Tides of Time I went into a bit more detail about who Saint Chyan was, and the truth behind his legend. His story didn't make it into the finished book, but it's part of the history of the Autumn Isles. Maybe it will come in useful one day.

Saint Chyan and the Lady of the Deep

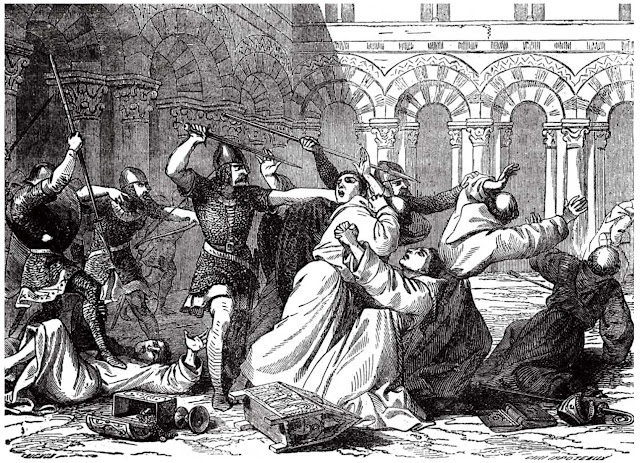

Of all the monks at his abbey, Brother Chyan was the laziest, and the least devoted. That was how he had come to be dozing by the river on the day the Northmen came. It was a sunny morning in the September of the year 834, and he should have been about his chores in the kitchen garden, but digging bean-rows was hard, and the green shade beneath the willows had called to him, and bade him put down his spade and slip away. He had taken off his sandals and bathed his feet in the slow-flowing river, then lay back on the grass and let the sun shine dim stained glass colours through his closed eyelids. By the time he sat up to see what all the far-off shouting was about, it was no longer far-off. The abbey was burning, the other monks were slain or fled away, and the heathen raiders caught Brother Chyan as easily as a poacher snatches up a startled rabbit.

It was God’s punishment, he supposed. He had shirked his holy duties, and now he must pay for it. To be trussed like a beast, to be hurled about in the wet bilges of a leaky longship, these were but a foretaste of the torments which awaited him in Hell.

The Northmen had been raiding along the coasts of Wessex all summer. Now they were on their way home to their nest near Dublin. They were carrying some looted silver ornaments from Christian churches, a couple of cows, and Brother Chyan, but it was a poor haul, and they did not seem happy. They spent most of the voyage arguing in their guttural, ungodly tongue. Brother Chyan lay on the ship’s bottom, soaked with bilge water and soiled with the dung of the cows, trying to keep out of the their way as they stomped angrily to and fro. Their talk sounded to him like the snarling of fierce dogs. He wondered if they were they discussing their plans for him. Was he be sold as a slave? Or would he become a martyr, sacrificed in some slow and dreadful manner to their heathen gods?

But it turned out the sea had plans of its own for Brother Chyan. As the ship rounded Land’s End an unseasonal storm rose up, and instead of sailing home to Dublin the Northmen were carried cursing way out into the western ocean.

Days and nights went howling by, the daylight barely lighter than the dark, the rain horizontal, the grey-green waves breaking over the ship and filling it like a bath tub. The wind in its fury ripped the sail to ribbons. The Northmen bellowed what Brother Chyan took to be prayers, and when their gods ignored him they untied Brother Chyan and shoved him to the ship’s bow, telling him by means of cuffs and gestures to pray to his White Christ for help.

That was how he came to be free when the great wave struck.

Brother Chyan was used to big waves by then, but this one was so huge that he thought at first it must be dry land looming. Seen through the spray as it rolled towards him, it looked less like water, more like a cliff of mottled grey stone rising precipitously from the deep. The ship began to climb it, then gave up the effort and turned sideways so that the avalanche of descending foam struck it side on and flipped it upside down.

It was strangely quiet beneath the wave, which came as a relief after the howling days of tempest up above. The Northmen, weighed down by their loot, their sea boots, and their many sins, sank like stones. Only trails of bubbles marked their passage into the dark below, and even those soon faded. But plump Brother Chyan, wearing only his homespun robe, bobbed back to the surface. There he saw the sheen of the ship’s upturned hull like a rain-wet roof, and one scared cow floundering and mooing. Another wave buried him, but again he surfaced, further from the ship this time. The cow was closer though, and the next time he went under one of its flailing flailing hooves clubbed him so hard behind the ear that he lost consciousness for a moment.

When he woke, he was still beneath the sea, but there was light all around him. Hampered by his soggy robe, he turned himself around. And there before him was the Blessed Virgin Mary herself, hanging in the luminous spaces of the sea much as she had hung in the sky on the painting on the chapel wall at the abbey.

At least, Brother Chyan assumed she must be the Blessed Virgin. For what other lady could be floating there, smiling so serenely at him, so deep under the ocean? What other lady would make it her business to attend the last moments of a drowning monk? Yet certain details struck him as peculiar. For instance, she was not wearing the blue gown he would have expected. She was not wearing anything at all except her own long hair, which swirled around her head like a dark halo, sometimes hiding and sometimes revealing her pale face. Her eyes, sea grey, regarded him with neither kindness nor concern.

But who was Brother Chyan to say whether the Queen of Heaven should wear a blue dress, or any sort of dress at all? And why should She show kindness to him, the least and laziest of all her servants? He tried to ask forgiveness, but as soon as he opened his mouth the air rushed out and the water rushed in.

The lady watched him while he flailed and gurgled. Her sea-grey eyes turned first to turquoise, then to summer blue. She watched his strugglings with what seemed to Brother Chyan more like amusement than pity. But at the last, as his sight was dimming and he felt the deeps begin to draw him down, she reached out her long white hands, and the sea took hold of him and thrust him up and out into the air again. A wave heaved him high, and he saw that the Northmen’s vanished ship had somehow righted itself. He was swept towards it like a leaf in a mill-race. One of the cows, wide-eyed and lowing, floundered past him down the wave’s steep face. Brother Chyan snatched hold of its tail as it went by, and they fetched up beside the ship together. He scrambled in over its side, leaving the cow to make its own arrangements. Huge waves roared around him in white ruin, lifting and turning the ship, hurling it towards a mountainous island, which had appeared as if from nowhere, surprisingly near. There was a cluster of straw-roofed huts planted like bee-hives on the sward behind the beach. People were emerging from the huts, staring in wonder as the vast wave rushed towards them, then starting to run as it came booming up the beach. The ship it carried was dragged rasping over rocks, until it came to rest a few yards from the huts. The wave withdrew and left it there.

The storm seemed spent. Out on the western ocean, small patches of sunlight had appeared. The ship slowly tilted over on its side, spilling out water, and a cow, and a solitary, soggy, very shaken monk.

The people of the island stood watching in silence. The ship had landed square upon a temple which had stood just seaward of their huts. The ring of stones and driftwood totems had been scattered like skittles. Brother Chyan’s first impulse, as he looked about him at the ruins, was to apologise. Then he remembered that destroying heathen temples was the duty of a good Christian.

So he raised his trembling arms, and said in the loudest voice that he could muster, “A miracle! I have been delivered from the rage of the Northmen and the fury of the storm for a great purpose…”

The Gorm, riding the swell just offshore with her long black hair spread out around her like a raft of weed, could not remember now what had prompted her to save the silly man. But her moods were ever thus; they shifted as swiftly as the patterns of foam upon the surface of her sea. So she left Brother Chyan to his new flock, and dove back into the deep.

Comments