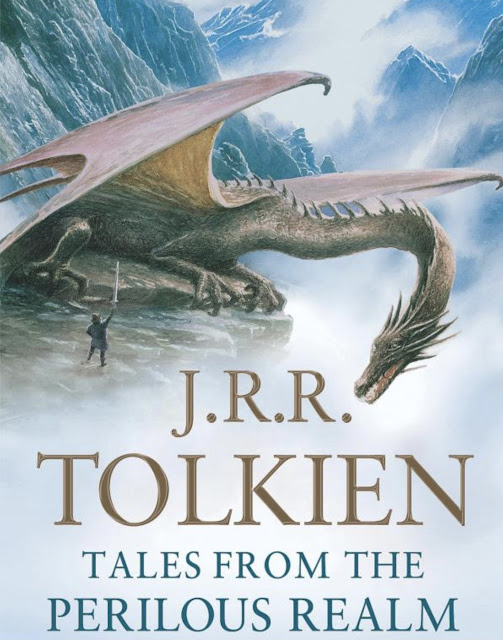

One of the stories in this collection is Leaf by Niggle, an allegorical tale about an artist in which Tolkien is plainly expressing his anxiety that his work of creating Middle Earth will never be finished and that what fragments he does manage to produce will be ignored by most people and eventually forgotten altogether. It’s quite affecting, and I suppose he never did finish it, but there seems little danger of it being forgotten, since all his notes and half-finished stories are now available as pricey books. This one, Tales from the Perilous Realm, comes with a beautiful Alan Lee painting of a hero confronting a dragon on the front, perhaps designed to nudge the unwary purchaser into thinking they’re buying something Lord of the Rings related. What they’ll actually be taking home is an anthology of short tales which were mostly available as separate small volumes when I was a young ‘un, bulked out with Tolkien’s essay On Fairy Tales.

Farmer Giles of Ham is the central story, and Farmer Giles is the hero confronting the dragon on the cover and end-papers. The story of how he becomes a dragon-fighter is an amiable tale with a rather Hobbitty feel - it could almost be set in the Shire, though the actual setting is a mythical England after the Romans but before King Arthur (although the historical mis-en-scene is loose enough to allow for a blunderbuss to feature; it reminded me slightly of TH White).

It’s followed by Smith of Wooton Major, which is more serious in tone. Its central character is allowed to wander into the land of Faery, and is forever haunted by the things he finds there. (For someone who disliked allegories, Tolkien seems to have cranked out a fair few of them.) There’s a Burne-Jones-ish air of Victorian romanticism, and some moments which wouldn’t feel out of place in Middle Earth, like the ‘Sea of Windless Storm where the blue waves like snow-clad hills roll silently out of Unlight to the long strand, bearing the white ships that return from battles on the Dark Marches of which men know nothing.’

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil is a group of poems, the first two about Bombadil, the others linked by the conceit that they were written in the Shire, by Bilbo, Sam Gamgee, and others. A few appear in The Lord of the Rings - Oliphaunt and The Man in the Moon - and most feel at least LOTR-adjacent. One outlier is Errantry, a comic-fantastic quest poem with a cheerful rhythm and an absolute delight in words and the sounds they make: it would be worth learning by heart. The Last Ship ends the collection on a note of Tennysonian melancholy.

But the best of the bunch here for me - or, at least, the most unexpected - is Roverandom, which I had heard of, but never read. It was written (as a fair few children’s stories are, and as none of mine ever had to be, thank Heavens) to console a child for the loss of a favourite toy. Tolkien’s son had lost his toy dog on Filey beach, and so his father spun a story about how it had actually been a real dog, enchanted by a tetchy wizard. Having been left behind, Rover goes on to have wild adventures on the moon and in the depths of the sea. It’s beautifully told, with that slightly laborious but still very charming whimsy you often find in Edwardian children’s fiction. The places Rover travels to are nothing like Middle-earth, and yet they are, because they’re brought to life through similarly brilliant layerings of detail upon detail. The disagreeable giant spiders who spin their webs among the mountains of the moon feel like relatives of Shelob, and at one point, when a friendly whale carries him far, far into the western sea, Rover glimpses ‘far off in the West the Mountains of Elvenhome and the light of Faery upon the waves’ and ‘the city of the Elves on the green hill beneath the Mountains, a glint of white far away’. But, that moment aside, the tone is generally comic, sometimes almost satirical. Alan Lee provides some lovely pencil drawings, but I think the story would work well in a separate volume, more heavily and humorously illustrated. (Sarah McIntyre would be perfect for the job - there are even some plump mermaids.) Anyway, track it down, and read it, and read it to your children.

Comments