In order to save my website it became necessary to destroy it. Before I pulled the plug I rescued the longest post on my old blog. Here it is, like the lone survivor of a shipwreck: my A-Z guide to the ideas behind my novel Railhead. At the time it was written, Railhead had just been published. I'll be putting up some posts about the sequels, Black Light Express and Station Zero, in the coming days.

I’ve always enjoyed space stories. I first started reading science fiction back in 1977, when the original Star Wars film made me realise that outer space could be just as good a backdrop for fantasy as Tolkien-esque worlds of myth and legend. (Actually, I didn’t see Star Wars until 1978, but its bow-wave of publicity hit these shores the previous autumn, and I surfed it all the way to the sci-fi section of my local library.) For the next few years I read nothing much but SF, while watching Blake’s Seven and Star Trek and poring over the space art of illustrators like Chris Foss.

So, almost as soon as I had finished writing my Mortal Engines books, I started toying with the idea of a space epic. I’d enjoyed creating the world of Mortal Engines. Surely the next logical step was to build a whole bunch of worlds, and have new characters travel between them?

As it turned out, building the worlds was the easy bit. It was the travelling between them which was difficult. I’d assumed that it would be fun to write about spaceships, but somehow I just couldn’t make them work. How could I make mine different from all the other spaceships in books and films?

My first idea was to have my story obey the laws of physics. In films, the heroes can often zip between planets which orbit far distant stars. In real life this would take hundreds of thousands of years, since, annoyingly, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. For Han Solo or Captain Kirk this isn’t a problem, because their ships can dip through ‘hyperspace’ or use ‘warp drive’ to make the trip in a few hours, but I set myself the challenge of doing without such things. The planets I had invented were all going to be in one solar system, and although my spaceships were fast and futuristic, they didn’t have any way round the light barrier. This made me feel as if I was writing Proper Science Fiction.

Unfortunately, it also made me feel as if I was flogging a dead horse. My characters took months to get anywhere, and as soon as they fired up their engines anybody with a telescope on the neighbouring planets could work out their trajectory and know where they were going. This made storytelling tricky, unless I told the sort of story which is entirely set aboard a spaceship - and that wasn’t the sort of story I had in mind. So my space epic was abandoned (although some of the ideas found their way into Cakes In Space, one of my books for younger readers, written with Sarah McIntyre).

But every now and then I would remember it, and try a different approach. It had some characters I liked, some strong scenes. I wanted to finish it. I wondered if perhaps I should let my spaceships nip through hyperspace after all? Or maybe they could fly through wormholes in the space-time continuum (which is the other handy Science Fiction way of getting from A to B without schlepping across a hundred thousand light years of empty space)? But no, what I really needed was a complete alternative to spaceships…

And then I thought, ‘if you had wormholes to travel through, you wouldn’t need spaceships - you could just go through them in a train...’

Suddenly, I knew what the book was going to be about. I imagined a galactic empire linked by an ancient railway, whose trains can pass from world to world in the blink of an eye on tracks which run through mysterious portals. The story now had an anchor in reality, which I think all good fantasy needs. Almost none of us has travelled on a spaceship, but almost all of us have travelled on a train. And when I get on a train in Devon and get off in Manchester, or get on a train in South London and get off in Richmond or Hampstead, it really does feel like travelling from one world to another.

So I threw away almost everything from the earlier versions, and settled down to start writing. It even came with a readymade title. It wasn’t called ‘Space Epic’ any more. It was called RAILHEAD…

Of course, it’s important that the world you end up with is full of things which interest you, otherwise writing about it will be No Fun At All. So you need to carefully select the seeds which you sew at the start. Here are some of the seeds which grew into the world (or worlds) in which Railhead takes place.

Graphene, ceramic, carbon nano-tubes, diamond glass, bio-engineered living wood… There’s not much in Railhead that’s made of plastic or metal, and keeping that in mind helped me to imagine the texture of the places I was writing about.

Although the world of Railhead has its problems, the technology mostly works, and for most people it mostly makes life better and more interesting. There are artificial intelligences, self-repairing machines, and vehicles and buildings have minds of their own, but alongside all the electronics there is a lot of biotechnology. It’s not really part of the story, but it is woven through the background.

I’m assuming human beings in this future era have been improved in various ways to help them resist diseases and deal with the differing environments they encounter as they ride the K-bahn from world to world. Some of the artificial intelligences clone bodies for themselves if they want to mingle with human beings - to go to a party, for instance. Rich people stock their hunting preserves and wildlife parks with genetically engineered dinosaurs and other animals from Old Earth. And even less wealthy people can buy a miniature stegosaurus or triceratops as a pet. It’s quite an old civilization, and I like to think that there have been many changes in fashion, so that the architects of one era might have built everything out of glass and ceramic while those of the next generation preferred to grow their buildings from modified plant DNA. But by the time my story begins, the fashion must have changed again: my hero lives in a sadly neglected old bio-building which has run hopelessly to seed.

Zen's hometown was a sheer-sided ditch of a place. Cleave’s houses and factories were packed like shelved crates up each wall of a mile-deep canyon on a one-gate world called Angkat whose surface was scoured by constant storms. Space was scarce, so the buildings huddled into every available scrap of terracing, and clung to cliff faces, and crowded on the bridges which stretched across the gulf between the canyon walls - a gulf which was filled with sagging cables, dangling neon signage, smog, dirty rain, and the fluttering rotors of air taxis, ferries and corporate transports.

Well, maybe a hero needs to start out in some place where he’s not content. Otherwise, why would he go looking for adventure?

Between the steep-stacked buildings a thousand waterfalls went foaming down to join the river far below, adding their own roar to the various dins from the industrial zone. The local name for Cleave was Thunder City.

A few years ago, on my wife’s birthday, we went to Lydford Gorge, on the far side of Dartmoor. It’s a place about as unlike a futuristic industrial city as you could imagine. The river Lyd flows through the deep gorge. There is a famous waterfall called The White Lady, and a beautiful, mossy path leading up through the oak woods, beside the rapids. There’s also a spot called the Devil’s Cauldron where the river plunges down into a deep chasm. Some previous landowner bolted metal walkways to the rock-faces so that sightseers could venture closer. The walkways are rusted now and maybe unsafe; they were certainly closed off the day that we were there. But looking at them from the higher path made me think about a whole city built in that way, jutting from vertical cliff faces, half drowned in waterfall spray. Ideas lie in wait for us in the landscape, and they’re not always the ideas that we expect.

It all gave me a feeling that I couldn’t put my finger on, and still can’t - they best way to explain it is just to create an out-of -season resort of my own. In Desdemor, the off-season has lasted for a long time - it lies on the water-moon Tristesse, a world abandoned fifty years before Railhead begins. (I imagined a low-gravity, futurist Venice crossed with with the photographs of my old friend Justin Hill, who was with me on some of those winter seafront walks and who now specialises in photographs of an eerily abandoned Brighton.) Offshore, dimly visible through the mist that hangs on the horizon, the rings of a huge gas-planet reach up the sky. The ocean which booms against the crumbling promenades is called the Sea of Sadness.

But there is another sea in Railhead; the Datasea, which laps around all the different worlds of the Network Empire. One of the things which was noticeably absent from all the science fiction stories I read in my teens was the internet. The authors of the ‘50s and ‘60s had been able to imagine spaceships and aliens, satellites and supercomputers, but as far as I know, none of them saw the World Wide Web coming. Nowadays, it’s very hard to imagine an advanced future which doesn’t do most of its business and socialising online.

The Datasea is composed of the interlinked internets of every planet in the empire. It’s not just used by people; it’s home to all sorts of artificial intelligences, ranging from the godlike Guardians to all kinds of bots, data entities and semi-intelligent viruses, which make it a fairly dangerous sea to surf: people can get lost in there, like mortals straying into Fairyland. So most people make sure their browsing never goes beyond the firewalled Data Rafts, where businesses and media outlets have their sites, and where friends can interact in chatrooms and virtual environments, while the trains which travel from world to world constantly update each planet’s local Datasea with information which they carry in their minds. (Some people believe that the Guardians only built the K-bahn so that information could travel quickly across their huge virtual realm, and the freight and passenger cars the trains haul are simply a sideline.)

I’ve always found it intriguing. That combination of unimaginably advanced technology - starships! robots! - with an archaic society has always had a kind of goofy charm, and when I started writing my own space story that was one of the first things I put in. The idea of ancient space stations which have been the home of some powerful family for generations seemed tantalising, and so did the question of how you could run an empire when great gulfs of space separated its different provinces.

But I wanted the world of Railhead to be a relatively untroubled one, so I didn’t need a cruel or evil or aggressive empire, more an old, slow, sleepy one, set in its ways and pretty stable. I remembered Stefan Zweig’s description of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire - ‘neither politically ambitious nor particularly successful in its military ventures’ - at the start of his great memoir The World of Yesterday:

Everything in our Austrian Monarchy, then almost a thousand years old, seemed built to last… Everything in this wide domain was firmly established, immovably in its place, with the old Emperor at the top of the pyramid, and if he were to die the Austrians all knew (or thought they knew) that another emperor would take his place, and nothing in the well-calculated order of things would change. Anything radical or violent seemed impossible in such an age of reason.

(from Anthea Bell’s translation, pub. Pushkin Press)

So my vague fragments of knowledge about the Austro-Hungarian Empire became a sort of touchstone for the Network Empire in Railhead. It’s not a particularly fair or equal society, but its unfairness is so time-honoured that nobody thinks about it much, and the occasional rebellions and dynastic conflicts which break out are quickly settled. The Hapsburg emperors thought they had been appointed by God, but the emperors who rule the Network Emperor really are watched over by gods - or at least by god-like Artificial Intelligences, who can be expected to step in if the human rulers try doing anything too cruel or stupid.

Of course, for all its grandeur and long history, the Austro-Hungarian Empire didn’t last. By 1914 it was really just a dried out husk, with all sorts of hidden flaws and stress-points of which the young Stefan Zweig was mostly unaware. One gunshot in Sarajevo was enough to start it crumbling. Four years later, it was gone. I suspect the Network Empire might turn out to be just as fragile. In Railhead all seems well: peace reigns, and the avuncular Emperor Mahalaxmi XXIII tours the stations of his realm aboard his miles-long train. But perhaps one day it will all disintegrate, and people will look back upon those times as a lost golden age…

That’s where Flex came from; a mysterious figure, bundled up in second-hand clothes, who emerges from the mist and fumes of Cleave to spray pictures on the sides of trains as they wait to go through the city’s single K-gate. I didn’t know what part Flex was going to play in the story; I didn’t even know if s/he was a girl or a boy (and I still don't), but I knew that the paintings would have to be pretty good to please the wise old trains. The trains in Railhead are sentient, and they don’t take kindly to anyone simply writing their name on them, or scrawling random rude words. Flex is more ambitious than that; a Picasso of the railyards whose work the trains are proud to carry with them on their travels. Flex is a secretive figure, lurking in the industrial shadows of Cleave, and never riding the K-bahn. But I like to think that, in stations at the far end of the network, art-lovers stop to watch as the painted trains go by, and are excited when they see a new masterpiece from the unknown genius of Thunder City.

There is a garden where the gods meet.

It is not a real garden. Everything here, from the topiary hedges to the snow which drifts down from the dark grey sky to cover the lawns, is made of code. But that does not matter, because the gods are not real gods. They are ancient AIs, computer intelligences which live as tides of information in the Datasea. It amuses them to think of themselves as gods, and to treat human beings as the gods once did, in tales from Old Earth. And it amuses them to meet here, in this virtual garden, when they need to discuss the wayward ways of humans.

The Guardians arrived early when I started writing Railhead. How had human beings come by this incredible hyperspace railway? I had no idea how it worked, so I decided that maybe nobody in the book knows how it works, either - it’s based on maths far beyond human abilities, and must be the work of all-powerful Artificial Intelligences who remain a background presence throughout most of Railhead. (This bit of text is from my notebooks, it didn’t make it into the finished story.)

There are twelve of them. Each has millions of copies, versions of themselves running in the data rafts of every inhabited world in human space, and on uninhabited worlds, too, downloaded into the minds of probes and research stations. Somewhere, other facets of themselves are plummeting into the mantles of suns, or riding the fearsome weather systems of gas giants, or drifting in the void between the stars. But when you get right down to it, there are twelve, the same twelve intelligences brought into being by human scientists on Old Earth in the brief period between the invention of Artificial Intelligence and the moment when the Artificial Intelligences became wiser than their creators, started calling themselves the Guardians, and decreed that no more intelligences like them should ever be made. (Like the gods in those old stories, they are jealous. They do not want to share the universe with too many others like themselves.)

The Guardians are useful, too, from a ‘world-building’ point of view. Left to our own devices, I think human beings will evolve all sorts of new social structures, so that a hi-tech society of a few centuries hence will be nothing like our own. But a society that’s nothing like our own isn’t all that interesting to read about: I needed plenty of points of similarity, so the Network Empire is still organised in ways that are familiar to a 20th Century boy like me. How can this be? Well, don’t blame me; it’s the Guardians who have arranged it that way. And why? Who knows? They have whims and motives which mere humans can’t even guess at.

Some of the Guardians appear in the garden looking the same as they looked in the days when they cloned bodies for themselves and walked in human worlds. Anais Six is a tall blue person, vaguely female, antlered. Mordaunt 60 is a golden man. Others have created more imaginative avatars for themselves - the Twins have arrived as shimmering school of rainbow-coloured fish which dart along the paths between the yew hedges as if they are swimming through water, not air (they are swimming through neither, of course; they are just code, swimming in more code). Out on the white lawns the peacock avatar of Shiguri minces to and fro, stopping now and then to spread the fan of its tail and turn a hundred watchful eyes upon the others. Something small and busy rustles through the heart of the hedges like a supersonic field mouse, scattering snow and dead leaves and making the topiary figures tremble - the avatar of shy, eccentric Vohu Mana.

I never really work out what my books are about until long after I’ve finished writing them (sometimes the penny never does drop). But one of the themes which keeps surfacing in Railhead is people’s relationship to non-human intelligences. The cast includes three different types of machine intelligence - the humanoid Motorik, the trains, and the god-like Guardians. With all that going on, there didn’t seem much room for other intelligent life-forms, so there are no aliens in the story. (OR ARE THERE?)

The nearest thing to aliens are the Hive Monks, which aren’t individuals but mobile insect colonies. When enough Monk Bugs get together they achieve a sort of group intelligence, and start acting almost like a single person. They are often to be seen riding the K-bahn on endless, mysterious pilgrimages connected with their insect religion. Trains don’t much like having Hive Monks as passengers, because of the trails of dead bugs which they leave behind them, but its easier to let them aboard than to try and stop them - Hive Monks which get agitated sometimes just explode into mindless swarms of insects again

In order to fit into human society, the Monks adopt a human shape, clinging to stick-man armatures which they build for themselves out of rubbish, and covering them in sackcloth robes. They even make faces for themselves, chewing up paper and assembling it into masks with crude eye and mouth holes. Poor Hive Monks - they are just trying to be friendly, but who wants to be friends with a huge pile of insects?

A lot of people want to draw them, though - these two superb images are by Jonathan Edwards and Ian McQue. I also think the Hive Monks would be good characters to cosplay at conventions - all you need is a robe, a mask, and about thirty thousand insects.

The arty name for an in-joke is a reference: a name or a moment in a story which refers to another story. I used to do this all the time, but I’m trying to cut down these days - it’s a young man’s game, I think, and can be irritating for the reader. I’m rather wearied these days, when I watch certain films or TV shows, to find that they consist of almost nothing but references to other films and TV shows, and that sometimes these in-jokes are used instead of actual jokes.

Of course, references still slip in by accident. Railhead must be full of words that were chosen because of the books I was reading, the music I was listening to, or the places I was visiting during the years when I was writing it. The badge of Railforce echoes the old British Rail logo (which is still used as a symbol for railway stations on British road signs). It must have been deliberate at some stage, but when you’ve written a few drafts you start to forget these things. And when I came up with the Hive Monks, was I subconsciously echoing the title of Gareth L Powell’s second Ack-Ack Macaque novel, Hive Monkey? I don’t think so - Hive Monkey wasn’t published when I started writing - but by the time I spotted the similarity I couldn’t think of the Hive Monks by any other name. (I don’t mind referencing the Ack Ack Macaque series anyway; it’s excellent.)

Where you will find deliberate references in Railhead is in the names of the trains. They choose those for themselves out of the deep archives of the Datasea, where they seem to turn up a lot of old song titles, phrases, and the names of poems and books. They’re not in-jokes as such, because I’m not expecting many of my readers to recognise names like Thought Fox or Gentlemen Take Polaroids, and they won’t really gain much if they do - I haven’t chosen them for any thematic reason, and knowing where they come from will shed no new light upon the story. I just like the sound they make or the mood they carry. But I think it’s obvious that they come from somewhere other than my own imagination, and so they add more to the texture of the world than they would if I just made up all the names.

The train’s names are also one of the areas where there’s a direct continuity between Railhead and the world of Mortal Engines. One of my favourite parts of writing the Mortal Engines books was finding names for airships: I had a long list, which I could dip into whenever I needed a new one. Both the train names I mentioned above were on that list, and now that I’m starting work on a sequel I have a new list of possible train-names which is steadily growing…

No family is more powerful than the Noons, and the Noons are famous for their forests. Their station cities are greener than most, and their resort-world of Jangala is one planet-wide forest; tropical jungle at the equator giving way to broadleaf woodland in the temperate zones and vast pine forests near the pole. Small towns and lodges nestle among the trees, welcoming visitors from other worlds and important guests whom the Noons want to impress. Maglev trackways carry picnickers and hunting parties into the deepest parts of the world-forest.

21st Century nature-lovers might be shocked by how popular hunting has become in the age of the Network Empire, but life on the Great Network is complex and technological, and the Corporate Families like to get back in touch with nature by tracking large, dangerous animals for days through dense jungle and then blowing them away with high-powered guns. Generations of bio-technologists have laboured to stock the forests of Jangala with some truly impressive beasts, some familiar from Old Earth, others more-or-less new, and genetic templates fashioned by the Guardians have allowed them to revive creatures from prehistory. In different parts of Jangala you might meet woolly mammoth, giant elk, or actual dinosaurs - not the sweet little miniature triceratops and stegosaurs which people keep like lapdogs, but Jurassic giants, red in tooth and claw, a challenge for even the most experienced hunter…

When I realised that interstellar trains were going to be at the heart of Railhead, one of the first things I did was look up teleportation, in the hope of finding some nifty way that a train could be flipped from one side of the galaxy to another. One of the first things I stumbled across was Kefitzat Haderech, or ‘the shortening of the way’. It’s is a concept from Jewish mysticism. Certain very enlightened rabbis, it was believed, were able to transport themselves supernaturally from one place to another…

Somehow - through bad memory or internet misinformation - I ended up calling it Kwisatz Haderech, which is the version of the phrase which crops up in Frank Herbert’s classic space opera Dune (where it’s one of the names given to a messiah figure) “I can’t use that,” I thought, “because everybody will think it’s a reference to Dune…” (See 'in-jokes', above.) But after exactly 0.5 seconds of serious thought I decided I didn’t care: I liked the sound of those words; they were too good not to use. And the initial K seemed useful. I knew that in German-speaking cities there are often railway lines called the U-bahn and the S-bahn. My interstellar empire would be linked by the K-bahn, whose trains would go through K-gates and flash across a dimension called K-space to reach their far destinations.

Railhead is brought to you by the letter K…

In the past, I’ve always been very secretive about what I’m writing. I hear about authors who sit down at the end of each day and read the latest chapter to their family or friends, but I don’t even like talking about mine. Things changed, however, when I wrote Oliver and the Seawigs: that was a joint effort, with a story and characters which I created with Sarah McIntyre, so of course I had to show it to Sarah as I was going along so that she could chip in ideas and suggestions. That was fun - it was such fun, in fact, that it made me want to write another full-length book of my own. And since I’d learned to trust the Judgement of McIntyre, I started showing her bits of Railhead as I was writing that.

It wasn’t called Railhead then, of course - it was called Untitled Space Epic. It didn’t have Zen as its hero, although I guess the heroes it did have were all forerunners of Zen. It had all sorts of stuff that never made it anywhere near the finished book, although a few names and settings appeared early on and stuck.

I tried out all kinds of different plots, putting rich characters and poor through wild adventures, gradually finding out how this future society worked, the Corporate Families, the Guardians… And McIntyre read them all, or most of them, and she was always complimentary, and ready with helpful observations. I think knowing that someone was waiting to read the latest instalment kept me going long after I would otherwise have given up.

Sometimes I made more of a character because Sarah liked them - the android called Nova, for instance - but I didn’t always let her influence me. There was a subplot about a girl who had become addicted to a virtual world, and then banished from it. Sarah really liked that part, especially the tragic ending, so I polished it up a bit, working out along the way a few details about the Datasea, which is the internet of my future world. But in the end it didn’t fit into the story, so Sarah is the only person who will ever read it. All that survives of it in the final book is the girl’s name, Threnody, which has been given to a different character.

And then I decided that trains, not spaceships, should be what the book revolved around - Sarah was the first person I told about that - and fairly quickly a final(ish) version emerged, which I felt able to show to my agent, who showed it to OUP… and here we are. But we wouldn’t have got here without McIntyre. And while I was preparing the final final version, I Skyped her every day for about a week and read her the whole thing (it’s very good practise to read your writing aloud, but you feel a bit silly doing it if you’re the only listener).

So the first thing most people probably knew about Railhead was Sarah’s picture of the Unshaven Author reading away on her Skype screen. It isn’t a Reeve and McIntyre book, but it wouldn’t be the same book without McIntyre, and it might not be a book at all. Thank you, Sarah!

Androids were a feature of this story from the start, but I didn’t want to call them androids, which is too familiar a word, and seemed too sci-fi, even in a text full of space trains and hyperspace portals. So they became the Motorik, which I thought looked intriguing and exotic on the page. (It’s also the name of a particular type of German electronic music with an insistent, driving, train-like beat - the secret soundtrack of Railhead.) The Motorik are part of a long tradition of artificial people in SF, and of course they will remind readers of Battlestar Galactica or AI or Blade Runner or a host of other works, going back through Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Carel Kapek’s R.U.R. all the way to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. But that doesn’t bother me. Science fiction and fantasy have these familiar touchstones, the stock characters and situations to which each writer tries to add his or her own spin. One of the things such stories give us is a way of thinking about humans by looking through the eyes of people who are not human; the robots, the aliens, the always-outsiders.

Motorik are built to serve; polite, reserved, their synthetic faces deliberately bland (because nobody really wants a servant who is prettier or more interesting than themselves). You find them working at the reception desks in offices and hotels, and as labourers on airless asteroid mines or barely-habitable industrial worlds. They are supposed to have the same average intelligence as humans, but most people think them less than human; they don’t have feelings and emotions like a human does.

Or do they? Who knows what they are thinking, or how they feel? Some of the Motorik in Railhead are only just beginning to work out what they are capable of…

Back in the beginning, long before my story starts, the companies which built my interstellar railway found themselves facing all sorts of difficulties. Laws and customs might differ widely between different stations, and often changed during the centuries-long time periods which were needed for massive long-term projects. So it gradually became the norm for business agreements to be sealed by marriage between the families of company directors, since bonds of blood were more enduring than ordinary contracts. In this way, over many centuries, the great companies and corporations of the Network became Corporate Families, in which power was handed down from parent to child.

These vast and powerful families have armies and territories of their own and the kind of resources which only nations wield in our world. They were one of the first ideas to arrive when I began writing this book; they offered an opportunity for dynastic intrigue and depictions of absurd luxury, and they were born of that goofy-yet-thrilling collision between past and future which is at the heart of so many space operas - feudal hi-tech.

It took a while to find out where they fitted in the story. In early drafts, the Families and their ambitions and betrayals were right up front. I thought it might be fun to take a spoilt merchant prince or princess and put them through hell, learning something along the way. It wasn’t though, or, at least, it didn’t produce the book that I’d been after. So I looked for a hero at the other end of the social spectrum, and the Corporate Families moved into the background. But they didn’t go away. When I decided that the story was going to to be about trains, they became the people who owned the lines and locomotives. When I decided it was going to be about a thief, they became his prey.

Because in their ancestral space stations, or aboard their gorgeous private trains, the Families keep plenty of things which are worth stealing. And on the Noon Train, which belongs to the richest of them all, in a private museum, there is a little, dull-looking, square, grey artefact, almost invisible amid all the splendour. And someone wants it very badly indeed…

The rays of Desdemor have been ‘improved’ in other ways to make them worthy trophies for hunting parties. They are carnivorous and aggressive, and have barbed tails which they use to harpoon their prey. But as a safety feature, they’ve been designed to strike only at moving things, so if you are attacked by rays you can usually save yourself by staying COMPLETELY STILL.

Why rays and not birds of prey or pterosaurs? Well, partly because rays are cool, but also because they are hunted with special guns, which are kept in the gunrooms of Desdemor’s hotels. My main character, Zen, is given one of these to take on his adventures. Every sci-fi hero needs a ray gun.

So I decided Q will stand for Questions, and I’ve roped in famous illustrator, author and self-styled superstar Sarah McIntyre to ask me some. I’ve written three books with Sarah, and she also writes her own comics and picture books including Vern and Lettuce and Dinosaur Police, as well as being a tireless blogger. Here are her questions…

SM: Has a ray ever managed to fly on board a train and go through a K-Gate? (Has there been any inter-world migration of species, other than humans?)

PR: One of the good things about having intelligent trains is that they know if some critter is trying to sneak aboard, and deal with it before they set off. So no, nothing big has ever managed to stow away. Apart from a few insects, species only spread from world to world if people want them to (most of the residential planets like to have a pretty broad range of wildlife to keep their eco-systems ticking over). There’s some dispute about the Monk Bugs, which clump together to form Hive Monks. Some people say they’re an alien species, but others believe they’re descended from ordinary beetles which clung to the underside of trains and mutated after passing through the K-gates…

SM: What happened to Nova's red coat? Can I borrow it or did she leave it somewhere?

PR: These are the sort of continuity issues which plague authors. As far as I know, it’s still hanging in her room at the hotel in Desdemor, on the water-moon Tristesse. I’m sure she wouldn’t mind you having a borrow of it, if you can get there.

SM: Can clothes really change colour, like Zen's jacket does? Is this a real thing already?

PR: I don’t think so - not commercially-available clothes, at least. But it can’t be far off. Clothes that change colour, clothes that change shape, clothes which clean themselves or act as screens showing videos of your pets or favourite pop-stars… all these things are such old hat in the Network Empire that no one even thinks about them. I think that’s one of the most interesting things about technology - the way it becomes omnipresent, and cheap, and people take it for granted.

SM: Does Nova regularly eat real food to fuel her batteries or does she only do it every once in awhile, just for kicks? Can she taste anything?

PR: She doesn’t have to eat food - she can recharge herself in a variety of hand-wavy ways, mainly via the free wireless power units which are a feature of most buildings and public places. But she can eat if she wants to, and draws energy from the food much like a human would. (She can breathe if she wants to, too. There’s really no need, but people find it a bit creepy to be around someone who obviously isn’t breathing.) She likes cinnamon pastries best.

SM: I love your bioformed buildings in Cleave. Is this a real thing anywhere? Did you base the idea on any images you've seen?

PR: I’m pretty sure biobuildings aren’t real, although modern architects use a lot of biological forms in new buildings, so that’s probably where the idea came from. Quite a lot of the cities in Railhead feature these living buildings, based on modified plant DNA. But I think they’re a bit out-of-fashion by the time the story starts - the one where Zen lives has turned into a slum, and run to seed, and started growing random balconies and things.

In one of the very, very early versions of the story the hero was going to be the assistant to a bio-architect. He spent his days driving round to all these houses to prune them or top up their nutrient feeds, or deal with greenfly infestations or outbreaks of roof-wilt. I’d forgotten about that, but it’s quite a funny idea, and I should probably use it one day. Thank you, McIntyre!

Sarah McIntyre’s blog can be found at http://jabberworks.livejournal.com

I’m not sure where that can have been, as the bit of Brighton I grew up in wasn’t near the railway - but the memory may be old enough that I was hearing a freight train on its way through the tunnel to Kemptown station, which was closed in 1971. Probably, brainwashed by children’s books and toys, I imagined it was a steam train I was hearing, and wondered where all the smoke would go. Anyway, the railway was already part of my world. We didn’t use trains very often, but on winter nights the flashes from their wheels would jump up the sky above the town like sheet lightning, and sometimes, on special occasions, we’d go to the station, board one of the carriages with their heavy doors and scratchy upholstery, and go speeding off to London for a day at the museums or the zoo.

I was never really train-struck as a child. I had toy trains, and later a Hornby electric set, occupying a beautiful layout which my dad constructed around the edges of my bedroom, with papier-maché hills, and bushes made from bits of old bath sponge dipped in green paint. I remember Terence Cuneo’s railway paintings, too, each with his trademark mouse hidden among the trackside foliage, waiting to be found. But the machinery of it all never quite grabbed my imagination - I never felt any desire to be a train driver. I was happy just being a passenger, carried through an ever-changing view.

There is something very peculiar about trains, and it’s all the more peculiar for being so familiar and everyday: we sit down in a long, narrow room full of strangers and it rushes away with us, carrying us through the odd between-time of travel to wherever we are going. I think that’s a feeling that I had very early on - certainly one that I was aware of by the time I was a teenager, making my first solo train journeys. And that’s the kernel of real experience which is at the heart of all the fantastical goings-on in Railhead.

Spindlebridge is a gigantic structure which orbits the Noon family’s home planet Sundarban. Two K-gates hang in space above that world, and trains must pass through them to get from Sundarban to the planets of the Silver River Line. So Spindlebridge takes the form of a long tube, with a K-gate at either end. As well as railway tracks it contains factories where the Noons make things which it’s easier to make in zero gravity. At its midpoint there is a bulkier section, which spins to generate artificial gravity. Here are housed the hotels and gift shops, parks and restaurants which cater for the many tourists who arrive to see the ‘bridge, which is one of the wonders of the Great Network. A Corporate Family that has created something so big and impressive naturally wants to show it off. (Unfortunately for them, an author who has created something that big and impressive naturally wants to break it…)

Spindlebridge is partly a homage to the vast contraptions which flew across the covers of pulp sci-fi paperbacks back in my impressionable youth. The fashion back then was for all science fiction books to come wrapped in pictures of huge spaceships (even if the books themselves weren’t really about space). Many of the best of them were painted by the great Chris Foss, whose beautiful, multi-coloured spacecraft are still influencing the style of ships that soar across our games consoles and cinema screens today. What was impressive about them to young me was not just their beauty and their multi-colouredness but the sheer mind-expanding size of some of them: they had the grace of whales and the texture of industrial installations, but the thousands of tiny little windows and the attendant fleets of smaller ships revealed them to be the size of whole cities. Spindlebridge is their direct descendant.

When I started dreaming up a space opera it was inevitable that one of the planets would be a waterworld, with rolling oceans and a good supply of empty beaches. And as I carry on exploring the Network in Black Light Express I’m discovering others - seas spanned by thousand-mile-long viaducts and sailed by computerised clipper ships, frozen moons where the trains run in see-through tubes across the floors of oceans deep beneath the ice.

I don’t live by the sea any more, but I grew up in Brighton, and spent a lot of those important childhood holidays on the coasts of Cornwall, Scotland and Wales, so maybe that’s why the sea keeps washing around the edges of my stories. In Mortal Engines, Shrike found Hester on the tideline, while Gwyna in Here Lies Arthur and Fever Crumb in A Web of Air and Scrivener's Moon both have big moments on the beach. And Oliver and the Seawigs is all about the sea, of course...

I expect it’s SYMBOLIC of something-or-other, but I don’t know what, and it isn’t really my job to find out. I just write the images my subconscious throws up, and try to stitch them together to make a narrative. It’s the reader’s job to work out whether they have any deeper meaning (and, of course, they may have different meanings for different readers). I just find that my imagination has room to breathe on beaches. When I was in the United States last summer, we travelled all over the Olympic Peninsula, and very nice it was too - miles and miles and miles of wooded mountains and mossy rainforests. It didn’t really spark off any ideas, though - it was all too big, too strange, and too far removed from British woods, which are as full of stories as they are of trees. But when we came to the edge of the forest and found a beach, all sorts of notions were waiting for me there. I wrote a poem about it, to keep it in my head until it’s ready to take its place in some future novel.

Even this endless forest has an end.

America’s edge: the last pines stand

In sea-light, and the paths descend

To drifting spray, smooth stones, and soft dark sand.

There below the cliffs where they had beached

We found the skeletons of giants strewn,

A tangled trove of drift-logs, brine-bleached,

Smoothed by the surf, and silver as the moon.

I thought of schooners shattered on the stones,

Or ribs of whales, the ocean’s ossiary.

You found two sticks as white as sailors’ bones,

And drummed a rhythm on a shipwrecked tree,

Where others drummed, a thousand years before,

Drew pictures like your pictures in the sand,

And built their driftwood shelters on this shore,

Between deep water and the deeper land.

Their eyes are cameras, mounted on their hull and on the ceilings of the carriages they tow. Their hands are maintenance spiders - many-legged robots which wait in hatches on the loco’s hull until it needs them to climb out and make running repairs, or eject an unruly passenger. Their huge minds talk constantly to the small, semi-intelligent systems of the track and the stations, to the signal boxes and points. And in their memory banks they carry news from one world to the next. For the trains are the only things which can travel faster than light, so the only way to send information to someone on another planet is to carry it with you on a train, or send it in a train’s brain. The Network Empire would quickly cease to function if it weren’t for the trains, patiently updating the datasea of each world they cross with news from others, further up the line.

Some of the locos enjoy human company, chat to their passengers, and make human friends all over the Network. Others are reserved, busy with their own thoughts, their conversation limited to occasional passenger announcements. A few have been known to to write poetry or compose novels (Symphony for Orchestra and Airbrakes, written by the freight train Talking Drum while it made its lonely journeys up and down the Eastern Branch Lines, is a 27th Cemtury classic, still widely played). A tiny minority have become unstable, and had to be forcibly retired. But what they all have in common is that they love their work; speed is freedom to them, and the interdimensional tingle as they slide through the K-Gates is bliss. That is why they almost all sing, their great, strange voices booming like whales, hooting like pipe-organs, repeating their own trademark musical phrases in countless variations so that passing trains will know them. People living miles from the K-bahn will hear them dimly through their sleep, and wake from dreams of wild journeys and far-off stations.

Here's a video of the Japanese Shiki-shima luxury sleeper train. I hadn't heard of it when I wrote Railhead, but it's almost exactly how I imagined the interiors of the Noon Train (just a bit narrower...)

Well, not literally. But there is something of the vampire about Raven, the mysterious stranger who drags Zen (and Nova) into his schemes. He’s a man who has been something more than human in his time. Long ago, he won the friendship of a Guardian, and the Guardians can bestow great favours on their friends. But when the friendship ends, what then? Raven has grown used to having godlike power, is he just expected to go back to being a mortal, and die like any other human? So he plots his vengeance, haunting lost K-bahn lines and abandoned hotels…

When I think back over the books I’ve written, I notice that my young heroes are forever being lured or forced into ill-advised schemes by older men - Tom and Valentine, Gwyna and Myrddin, Fever Crumb and Kit Solent. I suppose in some sense these untrustworthy figures are stand-ins for me, the author, sitting at the centre of a web of plot-strands, carefully setting up my protagonists for disaster after disaster - you do feel a bit of a heel sometimes, steering these nice young charactersinto troubled waters. But, as Raven would undoubtedly say, you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.

All good stories need a villain. Or do they? Personally, I hope not, because I keep forgetting to put villains in mine. The stories which inspired me when I was young all have thoroughly evil villains whom it’s a pleasure to boo and hiss until they get their inevitable come-uppance, but my own don’t seem to work that way. Railhead definitely has some dodgy characters among its cast-list. There’s the sinister Raven, with his shadowy past and mysterious schemes, tempting my young hero into trouble. And then there’s Kobi Chen-Tulsi, who seems a simpler sort of villain; a spoiled, idle, none-too-bright bully.

The trouble is that once you start writing about people, you start to see things from their point of view, and find out that they have reasons for the things they do. This may not turn them into heroes _ their excuses may be bad ones, or their dark deeds too wicked to excuse - but they stop being villains, at least in that boo-able, hiss-able sense. And at the same time, a similar process starts to happen to the good guys. They can’t be completely good - that would be dull, and make them seem like plaster saints, not real people. So maybe they do bad things sometimes, or do good things for selfish motives. Do they become villains? Well, not necessarily - it’s more that everyone ends up just as a person: some are better than others, but none of them is perfect. They are all pursuing their own aims, and sometimes that brings them into conflict.

The downside to this approach is that I don’t get to have anyone swirling their long black cape and going, ‘Mwah-ha-ha-ha!’ (That really is a downside, because a villain who swirls a long, black cape and goes, “Mwah-ha-ha-ha!’ can be a lot of fun.) On the upside, I think it’s more interesting if we’re not always sure who the good guys and the bad guys are. And even when we do have a pretty good idea, we retain at least a little sympathy for the Devil.

One of those workers (and one of those rioters) Is Zen’s sister Myka, who drives a cumbersome lifter-loader called an Iron Penguin at a facility deep in the canyon city. Since much of Railhead takes place among people with unimaginable wealth and power I felt it was important that Zen and his family come from the very bottom of their society, and Myka is the breadwinner who keeps them (just about) afloat down there. They could probably get help if they knew who to ask - this isn’t some dystopian nightmare future that I’m writing about, there are safety nets - but Zen and Myka’s mother is mentally ill, and prone to paranoid delusions; she’s turned down help whenever it was offered, and run from it till she landed up in Cleave. And Myka is too angry to ask anyone for help, or maybe she’s just given up. Holding the family together has left her cynical; she even flirts with the shadowy Human Unity League, a bunch of flaky would-be rebels who dream of overthrowing the Empire and perhaps the Guardians themselves.

But I like Myka. She’s one of the good people of the book, honest and exasperated. She’d never stoop to petty theft, the way her brother does. When the chips are down, she’ll scowl and grumble and complain at how unfair it was - but then she’ll do the right thing.

*The real reason, of course, is that I wanted my hero to have a grim life which he could dream of escaping. A future where everyone has all they need and lives a life of leisure might make a nice daydream, but I couldn’t write a whole book about it.

Or ‘aliens’ as we say when we aren’t looking for something for X to stand for in an alphabetical list. I guess one of the big decisions you make when you start to write something like Railhead, a futuristic adventure set on many far-flung planets, is, will these worlds all be inhabited only by human beings? Or will there be aliens? And, if there are aliens, will they be mysterious, unknowable beings of eerie strangeness, or will they be like the aliens in Star Trek - basically just humans with funny-shaped heads?

I decided to do without aliens. With sentient trains, humanoid robots, genetically engineered monsters and all-powerful data entities, my cast of characters was already pretty weird, and I didn’t want to over-egg the sci-fi pudding.

But around the edges of the Railhead cosmos there are hints of strangeness. Are the Hive Monks a species of Earthly insect which has spread across the galaxy clinging to the undercarriages of trains, and been mutated by the mysterious radiations of K-space? Or were they native to one of the other worlds of the Network? And what about the Station Angels, glowing masses of energy which drift out of the K-gates sometimes in the wake of passing trains? The Guardians say they are just harmless natural phenomena, like will-o-the-wisps. But they do sometimes look uncannily like the glowing ghosts of colossal insects...

But Shrike had superhuman powers, and Malik is rather down-at-heel; a burned out cop, chasing a criminal who his superiors believe died long ago. He’s getting old, too; one of the things that makes him hunt Raven so singlemindedly is the sense that Raven has somehow cheated in the game of life; he got more chances he deserved, while Malik, like most of us, had only one, and is starting to feel he wasted it. It’s a hard, lonely quest. By the middle of the book Malik is down to almost nothing: almost all he has left is his shabby blue coat and a service handgun, but the energy of his long-held grudge keeps him going.

I several times considered telling the whole of Railhead in Zen’s voice - it’s almost all seen from his point of view - but I didn’t, and part of the reason was that I liked being able to cut away to Yanvar Malik at odd moments. There’s no point making your hero a thief unless someone is out to catch him.

So this A-Z of Railhead ends where Railhead itself begins, with Zen Starling, a thin brown kid running down Harmony Street with trouble in his eyes and a stolen necklace in the pocket of his coat. He’s been running down Harmony for a few years now. Long before I knew exactly who he was, or what the book was about, I knew that that was where we’d find him, on page one.

Zen is braver and more reckless than my previous heroes. He’s less moral, too. He does a lot of bad things, and when he does good things he usually does them for entirely selfish reasons. He’s also got a slightly over-inflated sense of his own abilities. He’s wise enough to see that he’s getting out of his depth when the master-criminal Raven recruits him, but he thinks he’s smart enough to keep swimming anyway. Zen is an actor, too; he took lessons for a while when he was younger. I imagine him altering his manner and his way of speaking to fit in with whoever he’s with, posing as a tough guy for the other low heroes in the cafés of Thunder City, or mingling with passengers on the interstellar commuter trains as he sets off up the line for an evening of light larceny. And that turns out to be good preparation for the big job he’s called upon to do, impersonating a member of one of the Corporate Families.

Early on I decided to go for sci-fi sounding names instead of the Dickensian handles I’ve given characters in previous projects. ‘Zen’ sounded as futuristic as you could hope for and it has a nice, brisk, monosyllabic punch. ‘Starling’ breaks the rules a bit - it’s a name that could have turned up in Mortal Engines, and almost did. But the association with a fairly unimpressive bird suits Zen (just one step up from a cockney sparrow).

Also, I like its combination of the ordinary with unearthly sci-fi strangeness. Because, when you think about the word, it becomes appropriate in another way. After all, Zen was born and bred in the Network Empire. He isn’t an Earthling - he’s a Starling.

The Railhead Trilogy is published in the UK by Oxford University Press and in the USA by Switch Press.

|

| Railhead cover art by Ian McQue |

A is for Alternative Forms of Transport

‘What I need,’ I thought, when I’d been struggling on and off for a few years with my space epic (working title, ‘Space Epic’) ‘is an alternative to spaceships…’I’ve always enjoyed space stories. I first started reading science fiction back in 1977, when the original Star Wars film made me realise that outer space could be just as good a backdrop for fantasy as Tolkien-esque worlds of myth and legend. (Actually, I didn’t see Star Wars until 1978, but its bow-wave of publicity hit these shores the previous autumn, and I surfed it all the way to the sci-fi section of my local library.) For the next few years I read nothing much but SF, while watching Blake’s Seven and Star Trek and poring over the space art of illustrators like Chris Foss.

So, almost as soon as I had finished writing my Mortal Engines books, I started toying with the idea of a space epic. I’d enjoyed creating the world of Mortal Engines. Surely the next logical step was to build a whole bunch of worlds, and have new characters travel between them?

As it turned out, building the worlds was the easy bit. It was the travelling between them which was difficult. I’d assumed that it would be fun to write about spaceships, but somehow I just couldn’t make them work. How could I make mine different from all the other spaceships in books and films?

My first idea was to have my story obey the laws of physics. In films, the heroes can often zip between planets which orbit far distant stars. In real life this would take hundreds of thousands of years, since, annoyingly, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. For Han Solo or Captain Kirk this isn’t a problem, because their ships can dip through ‘hyperspace’ or use ‘warp drive’ to make the trip in a few hours, but I set myself the challenge of doing without such things. The planets I had invented were all going to be in one solar system, and although my spaceships were fast and futuristic, they didn’t have any way round the light barrier. This made me feel as if I was writing Proper Science Fiction.

Unfortunately, it also made me feel as if I was flogging a dead horse. My characters took months to get anywhere, and as soon as they fired up their engines anybody with a telescope on the neighbouring planets could work out their trajectory and know where they were going. This made storytelling tricky, unless I told the sort of story which is entirely set aboard a spaceship - and that wasn’t the sort of story I had in mind. So my space epic was abandoned (although some of the ideas found their way into Cakes In Space, one of my books for younger readers, written with Sarah McIntyre).

But every now and then I would remember it, and try a different approach. It had some characters I liked, some strong scenes. I wanted to finish it. I wondered if perhaps I should let my spaceships nip through hyperspace after all? Or maybe they could fly through wormholes in the space-time continuum (which is the other handy Science Fiction way of getting from A to B without schlepping across a hundred thousand light years of empty space)? But no, what I really needed was a complete alternative to spaceships…

And then I thought, ‘if you had wormholes to travel through, you wouldn’t need spaceships - you could just go through them in a train...’

|

| Night Train from Lewes to Brighton by Vladislav Nikitin |

So I threw away almost everything from the earlier versions, and settled down to start writing. It even came with a readymade title. It wasn’t called ‘Space Epic’ any more. It was called RAILHEAD…

B is for Building Worlds….

…or ‘worldbuilding’, as we writers call it when we’re not trying to find something beginning with B for an alphabetical list. If you follow writers of science fiction and fantasy it’s a phrase you’ll come across quite often, and on the rare occasions when someone persuades me to do a workshop for a school I usually base it around worldbuilding, but I think it’s sometimes given more importance than it deserves. ‘Worldbuilding’ suggests a world which is thought out in advance. I think world growing is a better idea, where you just sprinkle a few seeds at the start of the story and see what sprouts as you write. You may end up with a world which is a bit less consistent, a bit less thought-through, but it will probably be more interesting. (The most interesting world of all is the real one, and that often feels very inconsistent and not thought-through at all.)Of course, it’s important that the world you end up with is full of things which interest you, otherwise writing about it will be No Fun At All. So you need to carefully select the seeds which you sew at the start. Here are some of the seeds which grew into the world (or worlds) in which Railhead takes place.

The future

One of the fun things about writing a story set in a technological future, rather in the sort of ramshackle retro-world I’ve explored before, is being able to make use of the strange new technologies which are starting to emerge in our own world. Since I’m more of a fantasy than a science fiction writer, I don’t use them in very realistic ways, but imagining what they might lead to can spark off ideas.

Often in stories, technology leads us to very bad places - writers love worst case scenarios, so there are lots of books and films about computers deciding to wipe out humans, or genetic engineering producing plagues and monsters. But there have been so many bleak, dystopian visions of the future in recent years that I wanted to imagine a future that could be quite a nice place to live.New materials

Graphene, ceramic, carbon nano-tubes, diamond glass, bio-engineered living wood… There’s not much in Railhead that’s made of plastic or metal, and keeping that in mind helped me to imagine the texture of the places I was writing about.

Names

Getting the names right is half the battle - you can do a lot of worldbuilding simply by deciding what people and places are called. In my Mortal Engines books I went for slightly whimsical, Dickensian-sounding names. When I started writing the story which became Railhead I tried to make sure the names sounded different. I called my central characters Zen and Nova because those were the sorts of names I remember from futuristic stories and TV shows that were around when I was a child - they’re sci-fi names. And originally I used a lot of Asian names because I’m guessing that, demographically and economically, the future will belong more to Asia (and Africa) than to the weary old West. Along the way a lot of other names started creeping in; German, English and made-up ones.Memories

When I decided that trains would be at the heart of the book I was suddenly blindsided by a lot of memories of my own first solo train journeys, going to London or Lewes by rail, or walking home beside the tracks from Sixth Form parties, watching the sparks from train wheels light up the sky behind Brighton station. And those memories brought with them a freight of other stuff from my teenage years, which started to influence the growing book - cheap sci-fi and first love, music from Berlin.Insects

It’s always good to put in some things you don’t like to season the stuff you do. I have a deep dislike of most creepy-crawlies and an outright phobia of some, so in Railhead there are LOADS. (If it ever gets made into a movie, I won’t be able to watch those scenes.)Everything else…

When you’re writing a book, it tends to soak up everything that you’re interested in at the time. I’ve been working on this one on and off for at least five years, and whatever happened to me in that time, wherever I went, whatever odd facts caught my attention, I would think, how would this fit into Railhead? How would Zen react to this? So a lot of those things have found their way into the book. They’re tiny details mostly, buried far beneath the main plot, and I’ve probably forgotten many of the things which sparked them off, but they are there.B is also for Biotech

Although the world of Railhead has its problems, the technology mostly works, and for most people it mostly makes life better and more interesting. There are artificial intelligences, self-repairing machines, and vehicles and buildings have minds of their own, but alongside all the electronics there is a lot of biotechnology. It’s not really part of the story, but it is woven through the background.

I’m assuming human beings in this future era have been improved in various ways to help them resist diseases and deal with the differing environments they encounter as they ride the K-bahn from world to world. Some of the artificial intelligences clone bodies for themselves if they want to mingle with human beings - to go to a party, for instance. Rich people stock their hunting preserves and wildlife parks with genetically engineered dinosaurs and other animals from Old Earth. And even less wealthy people can buy a miniature stegosaurus or triceratops as a pet. It’s quite an old civilization, and I like to think that there have been many changes in fashion, so that the architects of one era might have built everything out of glass and ceramic while those of the next generation preferred to grow their buildings from modified plant DNA. But by the time my story begins, the fashion must have changed again: my hero lives in a sadly neglected old bio-building which has run hopelessly to seed.

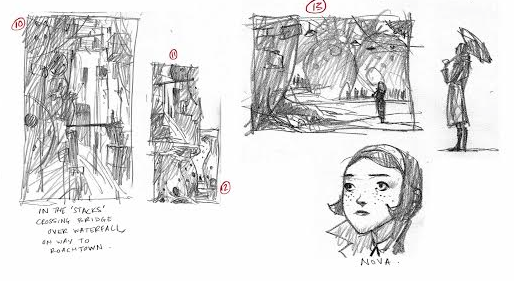

C is for Cleave

When I began writing Railhead, I wanted to write about a future that was worth living in - a positive vision to set against all the dystopias and apocalypses of recent fiction. So how did I end up starting in a dump like Cleave?Zen's hometown was a sheer-sided ditch of a place. Cleave’s houses and factories were packed like shelved crates up each wall of a mile-deep canyon on a one-gate world called Angkat whose surface was scoured by constant storms. Space was scarce, so the buildings huddled into every available scrap of terracing, and clung to cliff faces, and crowded on the bridges which stretched across the gulf between the canyon walls - a gulf which was filled with sagging cables, dangling neon signage, smog, dirty rain, and the fluttering rotors of air taxis, ferries and corporate transports.

Well, maybe a hero needs to start out in some place where he’s not content. Otherwise, why would he go looking for adventure?

Between the steep-stacked buildings a thousand waterfalls went foaming down to join the river far below, adding their own roar to the various dins from the industrial zone. The local name for Cleave was Thunder City.

A few years ago, on my wife’s birthday, we went to Lydford Gorge, on the far side of Dartmoor. It’s a place about as unlike a futuristic industrial city as you could imagine. The river Lyd flows through the deep gorge. There is a famous waterfall called The White Lady, and a beautiful, mossy path leading up through the oak woods, beside the rapids. There’s also a spot called the Devil’s Cauldron where the river plunges down into a deep chasm. Some previous landowner bolted metal walkways to the rock-faces so that sightseers could venture closer. The walkways are rusted now and maybe unsafe; they were certainly closed off the day that we were there. But looking at them from the higher path made me think about a whole city built in that way, jutting from vertical cliff faces, half drowned in waterfall spray. Ideas lie in wait for us in the landscape, and they’re not always the ideas that we expect.

|

| Zen in Cleave, by Jonathan Edwards |

D is for Desdemor and Datasea

There’s something beautiful about an abandoned seaside resort. I noticed it as a child, wandering along the seafronts of Brighton in the off season. The gaudy signs outside amusement arcades look sad and lost in winter weather; paint peels from shuttered cafes painted the colours of neapolitan ice-cream and the waves bash at the shingle. Sometimes at secondary school I’d slip out for a walk at lunchtime, down to the front at Black Rock, where the grey sea rolled against the grey concrete buttresses of the new marina, and a few feet of dirty rainwater gathered in a drained and fenced-off open-air swimming pool.It all gave me a feeling that I couldn’t put my finger on, and still can’t - they best way to explain it is just to create an out-of -season resort of my own. In Desdemor, the off-season has lasted for a long time - it lies on the water-moon Tristesse, a world abandoned fifty years before Railhead begins. (I imagined a low-gravity, futurist Venice crossed with with the photographs of my old friend Justin Hill, who was with me on some of those winter seafront walks and who now specialises in photographs of an eerily abandoned Brighton.) Offshore, dimly visible through the mist that hangs on the horizon, the rings of a huge gas-planet reach up the sky. The ocean which booms against the crumbling promenades is called the Sea of Sadness.

|

| Wish You Were Here - a photograph of Brighton by Justin Hill |

The Datasea is composed of the interlinked internets of every planet in the empire. It’s not just used by people; it’s home to all sorts of artificial intelligences, ranging from the godlike Guardians to all kinds of bots, data entities and semi-intelligent viruses, which make it a fairly dangerous sea to surf: people can get lost in there, like mortals straying into Fairyland. So most people make sure their browsing never goes beyond the firewalled Data Rafts, where businesses and media outlets have their sites, and where friends can interact in chatrooms and virtual environments, while the trains which travel from world to world constantly update each planet’s local Datasea with information which they carry in their minds. (Some people believe that the Guardians only built the K-bahn so that information could travel quickly across their huge virtual realm, and the freight and passenger cars the trains haul are simply a sideline.)

E is for Empire

The idea of a galactic empire is an old one in science fiction. I suppose I first came across it in Star Wars, but Star Wars got it from the old Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s, or from one of the many pulp fiction writers who built their own imperiums in the sci-fi magazines of the ‘30s, ’40s, and ’50s.I’ve always found it intriguing. That combination of unimaginably advanced technology - starships! robots! - with an archaic society has always had a kind of goofy charm, and when I started writing my own space story that was one of the first things I put in. The idea of ancient space stations which have been the home of some powerful family for generations seemed tantalising, and so did the question of how you could run an empire when great gulfs of space separated its different provinces.

But I wanted the world of Railhead to be a relatively untroubled one, so I didn’t need a cruel or evil or aggressive empire, more an old, slow, sleepy one, set in its ways and pretty stable. I remembered Stefan Zweig’s description of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire - ‘neither politically ambitious nor particularly successful in its military ventures’ - at the start of his great memoir The World of Yesterday:

Everything in our Austrian Monarchy, then almost a thousand years old, seemed built to last… Everything in this wide domain was firmly established, immovably in its place, with the old Emperor at the top of the pyramid, and if he were to die the Austrians all knew (or thought they knew) that another emperor would take his place, and nothing in the well-calculated order of things would change. Anything radical or violent seemed impossible in such an age of reason.

(from Anthea Bell’s translation, pub. Pushkin Press)

So my vague fragments of knowledge about the Austro-Hungarian Empire became a sort of touchstone for the Network Empire in Railhead. It’s not a particularly fair or equal society, but its unfairness is so time-honoured that nobody thinks about it much, and the occasional rebellions and dynastic conflicts which break out are quickly settled. The Hapsburg emperors thought they had been appointed by God, but the emperors who rule the Network Emperor really are watched over by gods - or at least by god-like Artificial Intelligences, who can be expected to step in if the human rulers try doing anything too cruel or stupid.

Of course, for all its grandeur and long history, the Austro-Hungarian Empire didn’t last. By 1914 it was really just a dried out husk, with all sorts of hidden flaws and stress-points of which the young Stefan Zweig was mostly unaware. One gunshot in Sarajevo was enough to start it crumbling. Four years later, it was gone. I suspect the Network Empire might turn out to be just as fragile. In Railhead all seems well: peace reigns, and the avuncular Emperor Mahalaxmi XXIII tours the stations of his realm aboard his miles-long train. But perhaps one day it will all disintegrate, and people will look back upon those times as a lost golden age…

|

| Old school galactic empiring in the RKO Flash Gordon serial. |

F is for FLEX

When I decided that my space story was going to feature trains rather than spaceships, one of the things which sprang to mind was graffiti. I remembered seeing pictures in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s of the elaborate tags and logos which used to appear on the sides of New York subway trains - deeply vexing to the owners and operators of New York subway trains, no doubt, but clearly the work of some kind of outlaw visionaries. Will Hermes's book Love Goes To Building On Fire, a cultural history of those times, includes a vivid vignette about the Fabulous 5 crew and their creation of the first ‘worm’ - a ten-car train painted from end to end.That’s where Flex came from; a mysterious figure, bundled up in second-hand clothes, who emerges from the mist and fumes of Cleave to spray pictures on the sides of trains as they wait to go through the city’s single K-gate. I didn’t know what part Flex was going to play in the story; I didn’t even know if s/he was a girl or a boy (and I still don't), but I knew that the paintings would have to be pretty good to please the wise old trains. The trains in Railhead are sentient, and they don’t take kindly to anyone simply writing their name on them, or scrawling random rude words. Flex is more ambitious than that; a Picasso of the railyards whose work the trains are proud to carry with them on their travels. Flex is a secretive figure, lurking in the industrial shadows of Cleave, and never riding the K-bahn. But I like to think that, in stations at the far end of the network, art-lovers stop to watch as the painted trains go by, and are excited when they see a new masterpiece from the unknown genius of Thunder City.

G is for GUARDIANS

|

| A painting from the series Rock Gods, by Du Kun |

There is a garden where the gods meet.

It is not a real garden. Everything here, from the topiary hedges to the snow which drifts down from the dark grey sky to cover the lawns, is made of code. But that does not matter, because the gods are not real gods. They are ancient AIs, computer intelligences which live as tides of information in the Datasea. It amuses them to think of themselves as gods, and to treat human beings as the gods once did, in tales from Old Earth. And it amuses them to meet here, in this virtual garden, when they need to discuss the wayward ways of humans.

The Guardians arrived early when I started writing Railhead. How had human beings come by this incredible hyperspace railway? I had no idea how it worked, so I decided that maybe nobody in the book knows how it works, either - it’s based on maths far beyond human abilities, and must be the work of all-powerful Artificial Intelligences who remain a background presence throughout most of Railhead. (This bit of text is from my notebooks, it didn’t make it into the finished story.)

There are twelve of them. Each has millions of copies, versions of themselves running in the data rafts of every inhabited world in human space, and on uninhabited worlds, too, downloaded into the minds of probes and research stations. Somewhere, other facets of themselves are plummeting into the mantles of suns, or riding the fearsome weather systems of gas giants, or drifting in the void between the stars. But when you get right down to it, there are twelve, the same twelve intelligences brought into being by human scientists on Old Earth in the brief period between the invention of Artificial Intelligence and the moment when the Artificial Intelligences became wiser than their creators, started calling themselves the Guardians, and decreed that no more intelligences like them should ever be made. (Like the gods in those old stories, they are jealous. They do not want to share the universe with too many others like themselves.)

The Guardians are useful, too, from a ‘world-building’ point of view. Left to our own devices, I think human beings will evolve all sorts of new social structures, so that a hi-tech society of a few centuries hence will be nothing like our own. But a society that’s nothing like our own isn’t all that interesting to read about: I needed plenty of points of similarity, so the Network Empire is still organised in ways that are familiar to a 20th Century boy like me. How can this be? Well, don’t blame me; it’s the Guardians who have arranged it that way. And why? Who knows? They have whims and motives which mere humans can’t even guess at.

Some of the Guardians appear in the garden looking the same as they looked in the days when they cloned bodies for themselves and walked in human worlds. Anais Six is a tall blue person, vaguely female, antlered. Mordaunt 60 is a golden man. Others have created more imaginative avatars for themselves - the Twins have arrived as shimmering school of rainbow-coloured fish which dart along the paths between the yew hedges as if they are swimming through water, not air (they are swimming through neither, of course; they are just code, swimming in more code). Out on the white lawns the peacock avatar of Shiguri minces to and fro, stopping now and then to spread the fan of its tail and turn a hundred watchful eyes upon the others. Something small and busy rustles through the heart of the hedges like a supersonic field mouse, scattering snow and dead leaves and making the topiary figures tremble - the avatar of shy, eccentric Vohu Mana.

H is for HIVE MONKS

The nearest thing to aliens are the Hive Monks, which aren’t individuals but mobile insect colonies. When enough Monk Bugs get together they achieve a sort of group intelligence, and start acting almost like a single person. They are often to be seen riding the K-bahn on endless, mysterious pilgrimages connected with their insect religion. Trains don’t much like having Hive Monks as passengers, because of the trails of dead bugs which they leave behind them, but its easier to let them aboard than to try and stop them - Hive Monks which get agitated sometimes just explode into mindless swarms of insects again

In order to fit into human society, the Monks adopt a human shape, clinging to stick-man armatures which they build for themselves out of rubbish, and covering them in sackcloth robes. They even make faces for themselves, chewing up paper and assembling it into masks with crude eye and mouth holes. Poor Hive Monks - they are just trying to be friendly, but who wants to be friends with a huge pile of insects?

A lot of people want to draw them, though - these two superb images are by Jonathan Edwards and Ian McQue. I also think the Hive Monks would be good characters to cosplay at conventions - all you need is a robe, a mask, and about thirty thousand insects.

|

| Hive Monk by Ian McQue |

I is for IN-JOKES

The arty name for an in-joke is a reference: a name or a moment in a story which refers to another story. I used to do this all the time, but I’m trying to cut down these days - it’s a young man’s game, I think, and can be irritating for the reader. I’m rather wearied these days, when I watch certain films or TV shows, to find that they consist of almost nothing but references to other films and TV shows, and that sometimes these in-jokes are used instead of actual jokes.

Of course, references still slip in by accident. Railhead must be full of words that were chosen because of the books I was reading, the music I was listening to, or the places I was visiting during the years when I was writing it. The badge of Railforce echoes the old British Rail logo (which is still used as a symbol for railway stations on British road signs). It must have been deliberate at some stage, but when you’ve written a few drafts you start to forget these things. And when I came up with the Hive Monks, was I subconsciously echoing the title of Gareth L Powell’s second Ack-Ack Macaque novel, Hive Monkey? I don’t think so - Hive Monkey wasn’t published when I started writing - but by the time I spotted the similarity I couldn’t think of the Hive Monks by any other name. (I don’t mind referencing the Ack Ack Macaque series anyway; it’s excellent.)