I am re-reading The Lord of the Rings and blogging about some of the vague half-formed thoughts that it sends flittering, moth-like, across my sensorium...

Hard and cruel and bitter was the land that met his gaze. Before his feet the highest ridge of the Ephel Dûath fell steeply in great cliffs down into a dark trough, on the further side of which there rose another ridge, much lower, its edge notched and jagged with crags like fangs that stood out black against the red light behind them: it was the grim Morgai, the inner ring of the fences of the land. Far beyond it, but almost straight ahead, across a wide lake of darkness dotted with tiny fires, there was a great burning glow, and from it rose in huge columns a swirling smoke, dusky red at the roots, black above where it merged into the billowing canopy that roofed in all the accursed land.

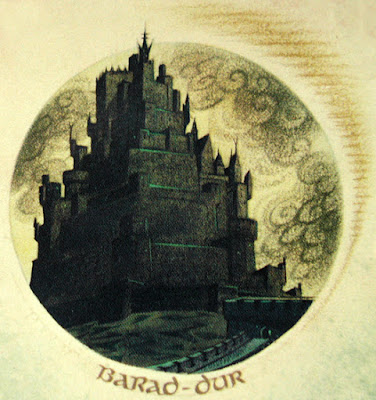

The illustration above is by Ted Nasmith, and very nice it is too. But in some ways it's a shame Tolkien wasn't writing fifty or sixty years earlier, when painters regularly turned to literature for subjects; imagine what John Martin could have done with Mordor. The Lord of the Rings, however, couldn't have been written fifty or sixty years earlier: for all its olde-worlde trappings it's a completely Twentieth Century vision, and in Mordor the hobbits will confront Tolkien's misgivings about modernity head on.

But first Sam has to work out how to rescue Frodo from a tower full of two hundred heavily armed orcs. Luckily, the heavily armed orcs are way ahead of him: they start squabbling over Frodo's coat of mithril mail and pretty much all kill each other. This struck me as unlikely turn of events when I first read the book, and I think I was on to something - in how many battles do both sides completely wipe each other out, (especially if they're fighting with with knives and bows rather than, say, battleships)? But it's been well established that orcs hate other orcs and are as likely to turn on each other as fight the enemy (they're a bit like the Labour Party that way). Also, Frodo's capture at the end of The Two Towers was a cracking cliff-hanger, and sometimes the price you pay for a cracking cliff-hanger at the end of an episode is that a little bit of fancy footwork is required at the start of the next to get our heroes to safety and the plot back on the road.

And what a road it is. Here's one in Iceland that looks a bit like it, only with a nice chair for weary travellers to rest on. (There are no nice chairs in Mordor.)

I had forgotten how many different bits of Mordor there are - the Morgai, Gorgoroth, the Isenmouthe, 'the the great slave-worked fields away south... beyond the fumes of the Mountain by the dark sad waters of Lake Núrnen.' I suppose it should come as no surprise that it's as crammed with detail as the Shire or Rohan. All the different bits of Mordor, however, are horrid; the only vegetation is thorn bushes and brambles, and there are stinging flies everywhere - some of them, in a rather brilliant detail, 'marked like orcs with a red eye-shaped blotch'. It's also a heavily militarised landscape, criss-crossed by troop roads along which endless regiments of orcs are marching towards the Black Gate and the battle which we saw at the end of Book One. There's more of that dystopian atmosphere I mentioned in my post before-last. Frodo's 'left hand would often be raised as if to... screen his shrinking eyes from a dreadful Eye that sought to look in them.' 'Don't you know we're at war?' bellows an orc NCO. It's as if Mordor is a vent through which the Twentieth Century is trying to force itself into Middle-earth.

|

| Pauline Baynes |

Earlier, even Sam sensed the temptation of the Ring:

Wild fantasies arose in his mind; and he saw Samwise the Strong, Hero of The Age, striding with a flaming sword across the darkened land, and armies flocking to his call as he marched to the overthrow of Barad-dûr. And then all the clouds rolled away, and the white sun shone, and at his command the vale of Gorgoroth became a garden of flowers and trees and brought forth fruit. He had only to put on the Ring and claim it for his own, and all this could be.

Although Tolkien scorned allegory, the Ring is a pretty good metaphor for power; everyone wants it, everyone thinks they will use it to make the world a better place, and everyone who actually gets it is corrupted by it.

Sam resists the temptation, and a good job too, because with Frodo weakened it's up to him to keep them on the road to Mount Doom. This is the section of the book where Sam comes into his own - he's loyal, steadfast, patient, kind, and unimaginative, but even that is a virtue in these circumstances. His love for Frodo is so intense, and so selfless, that modern readers can be forgiven for thinking they've spotted a Gay Subtext. I don't think they have have, though. Tolkien had endured the trenches, and is writing about a kind of intense comradeship which springs up between men who have faced death together. Nowadays a faint echo of that ideal lives on in buddy movies, but the heroes of those seldom hold hands or sleep in each other's arms, as Sam and Frodo do.

There's also in Sam's feelings for Frodo a strong element of what Bertie Wooster would call 'the old feudal spirit'. He is a good servant, devoted to his master. There are lots of them in novels (Sam may be one of the last of the type) but I suspect they appealed a lot more to people who had servants than those who were servants. If my grandparents had lived in Oxford they might have been emptying Professor Tolkien's bins or serving him pints at the Eagle & Child while he was writing his meisterwerk, so to me the loyal Sam can seem rather dog-like at times, faithfully adoring his Master in return for the occasional pat on the head. But Tolkien's affection and admiration for Sam seem genuine, and so does his belief in a social order in which benevolent masters like Frodo are served by doughty retainers like Sam. Sam knows his place. One of the things which allowed him to resist the Ring is that he simply understands such things aren't for the likes of him:

...deep down in him lived still unconquered his plain hobbit-sense: he knew in the core of his heart he was not large enough to bear such a burden, even if such visions were not a mere cheat to betray him. The one small garden of a free gardener was all his need and due...

The hobbits traverse what feels like a vast lava field - 'the whole surface of the plain of Gorgoroth was pocked with great holes, as if, while it was still a waste of soft mud, it had been smitten with a shower of bolts and huge slingstones'. When I was young this section felt long - not boring, just bleak and relentless. Actually it's quite brisk - only a couple of chapters - but the focus on Frodo's exhaustion and the descriptions of the harsh surroundings make you feel every step. There's also the growing realisation that this is a one-way trip - even if they make it to the volcano, they haven't enough food or strength to get back. The ascent of Mount Doom itself, with the grim vistas of Mordor opening up below, is even more gruelling. We have come so far and seen so much since Gandalf first mentioned the Cracks of Doom back in Frodo's peaceful study in the Shire, it seems impossible to believe that the Ringbearer has finally reached the end of his great journey.

But he has - and having got there, he finds that he can't fulfill his task: the Ring has triumphed, and he chooses not to throw it into the fires as arranged. So Gollum gets to play his final part in the story, biting off Frodo's finger, Ring and all, and then toppling into the fiery fissure while he gloats over it. 'Out of the depths came his last wail Precious, and he was gone.' Earlier, he attacked the hobbits as they climbed the mountain and was driven off when Frodo reminded him of the oath he had sworn on the Ring. Sam sees Frodo addressing Gollum then as 'a figure robed in white, but at its breast it held a wheel of fire. Out of the fire there spoke a commanding voice. 'Begone, and trouble me no more! If you touch me ever again you shall be cast yourself into the Fire of Doom.' And Gollum does, and he is, so the curse is fulfilled, but so is Gandalf's prediction that 'Even Gollum may have something yet to do'. It feels more like fate or providence lending a hand, and more important than Frodo's curse is the moment that follows; Frodo heads on up the mountain, leaving Sam to deal with Gollum. Frodo has spared Gollum's life on a number of occasions, when Sam was always inclined to kill him; now, standing over Gollum with a sword in his hand, Sam too elects to spare him - the act of mercy which enables the destruction of the Ring.

And with the Ring destroyed, so is Sauron, and so are all Sauron's works. The hobbits watch from the threshold of Sammath Naur as

Towers fell and mountains slid; walls crumbled and melted, crashing down; vast spires of smoke and spouting steams went billowing up, up, until they toppled like an overwhelming wave, and its wild crest came foaming down upon the land. (...) The skies burst into thunder seared with lightning. Down like lashing whips fell a torrent of black rain. And into the heart of the storm, with a cry that pierced all other sounds, tearing the clouds asunder, the Nazgûl came, shooting like flaming bolts, as caught in the fiery ruin of hill and sky they crackled, withered, and went out.

(The last time I read The Lord of the Rings I was reading it aloud to my son, who was then about eight or nine. He's not a bookish sort, but when we got to this bit he said, "That is SUCH GOOD WRITING." This is one of the advantages that a good book has over a movie: the special effects are better.)

|

| Pauline Baynes |

'a huge shape of shadow, impenetrable, lightning-crowned, filling all the sky. Enormous it reared above the world, and stretched out towards them a vast threatening hand, terrible but impotent: for even as it leaned over them, a great wind took it, and it was all blown away, and passed; and then a hush fell.'

So that is Sauron, The Lord of the Rings himself, putting in his one appearance in the book which is named after him.

In the 1970s the director John Boorman started developing a movie of The Lord of the Rings. Even to a Boorman fan like me it looks as if it would have been absolutely dreadful and we're very lucky it fell through and he ended up making Excalibur instead. But there is one goofy idea lurking in Boorman's treatment (co-written with Rospo Pallenberg) which I rather like: after Barad-dûr falls, 'on both sides, weapons are thrown down; all thought of war is gone, all heart for fighting, lost. The ORCS, rather like snakes, shed their scaled skins of armour, revealing themselves to have disgusting white slug-like skin, but rather human.' Tolkien's orcs either go mad and cast themselves into pits or run off to hide in 'holes and dark lightless places far from hope' - a pity, I think, I'd like to see a bit of orcy redemption going on at the end, or at least a chance of it.

Except this isn't the end, of course. Mount Doom has gone boom, Sauron and his Ring are destroyed, the eagles have rescued Sam and Frodo from what seemed Certain Death, Aragorn is installed as King of Gondor, Faramir and Éowyn get engaged, and in most fantasy novels it would be time for the author to type THE END and send it to the printers. But The Lord of the Rings isn't just a fantasy novel, or if it is, it's a fantasy novel which is contained inside another sort of novel entirely. I started writing this blog series because I was intrigued by the long, slow opening in the Shire - what is it for? Why is it there? It's balanced by the long, slow closing in the Shire, and that is where I think the book reveals it actual power and meaning. And that's where we'll be going in the next post.

There are lots more of Pauline Baynes's great illustrations for Tolkien (and C.S.Lewis, and many other authors) on her website here.

Comments

When I finished a slow re-read of LOTR recently, I have to say the thing that struck me more than anything else was how much of a leader Sam has become by Mordor. By the final stage Frodo is completely out of it and Sam is doing everything, not just the physical labour but making all the decisions, e.g. about the route and the supplies. To the extent even that I now sort of feel Sam is the protagonist of LOTR, not Frodo. Sam as the slow-witted loyal dog, the "Oooh, Mr Frowdow" rustic caricature - that is entirely how he's presented in the adaptations, and people have come up with all these explanations about friendships between officers and batmen in the trenches ... but to me it doesn't feel that was how Tolkien intended the character to be read.

P.S. Thanks again for this whole series. I can totally understand not wanting to post about the appendices, but do have another look at them if you can. Just as one example, I found the line about the white flowers growing on Helm's burial mound to be the most moving in the whole book - as you say, he had so many ideas that didn't even fit the main story.

One of the big questions about Tolkien is why he never finished The Silmarillion. The official answer is that he went down ever-deeper philosophical rabbit holes (are Orcs irredeemably evil? How can Elves be immortal yet age?) ... but I wonder if he really knew it was just never going to be as good as LOTR. The Silmarils themselves are the same concept of a beautiful object that causes people to do bad things that he repeated with the Arkenstone and the Rings of Power, but he did it best with the Rings.